So, what I'll post here is shorter summaries of my findings, as well as some insight into the actual process of research.

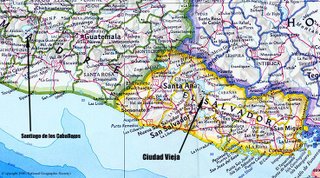

The name Ciudad Vieja refers to an archaeological site located 10 km south of Suchitoto, El Salvador. A number of archaeologists have worked on this site since the 1970s, but the largest amount of excavation, analysis, and study has occured since 1996 as the Ciudad Vieja Archaeological Project, directed by Dr. William Fowler of Vanderbilt University. I joined this project in 1999 as an excavator, but primarily as the project ceramicist, and my research forms the basis of my dissertation in Tulane University's anthropology doctoral program.

This site is the physical location and remains of the second villa (town) of San Salvador. Founded in 1528, six years after the first Spaniards cruised along the coast of what is now El Salvador, and three years after Spanish and Mexican forces commanded by the Alvarado family, this is the first permanent Spanish-controlled settlement in El Salvador. It is located in the northern edges of what had been the altepetl of Cuscatlan. An altepetl, a Nahuatl word meaning hill and water, was considered a proper place and polity, typically with a substantial town or city at the center. A small kingdom would be an altepetl with smaller communities subject to it, while larger cities and states could incorporate multiple altepetl. Ethnohistorian James Lockhart has done a lot of work on the atepetl amongst the Nahua of Central Mexico, cultural and linguistic cousins of the Pipil.

The Pipil were the main political and ethnic group in El Salvador in the early sixteenth century, and it was they who fielded troops to fight the invading Spaniards and Mexicans. They soon learned that open warfare against Spanish cavalry was suicide, and took to a solution used throughout Mesoamerica in the face of an overwhelming force: retreat to a high point. This shift to settlements on hilltops can be seen throughout Mesoamerica after the fall of Teotihuacan and later the Classic Maya cities, and the Spaniards wrote about the problems they had bringing hostile Mesoamericans down from these penoles during the sixteenth century.

I may revisit at later dates some of the historical events recorded for the villa of San Salvador, but it should be mentioned now that sometime around 1545, the town was abandoned as San Salvador was given the license to expand to a full city, and to move to its present location about 33 km to the south-southwest. The implications for the archaeology of Ciudad Vieja is that it presumably represents a single generation (17 years or so) of time, and the first generation of the Spanish invasion, conquest, and colonization of Central America.

This has influenced my research design from the very beginning. In some ways even more than history, archaeology has two major variables: time and space. Archaeology has adopted a tremendous amount from geography in order to deal with space. But for time, archaeology has turned to geology, art history, and chemistry amongst other sciences, adapting techniques from these fields. I have applied some of these techniques (though not chemical techniques such as radiocarbon decay dating) to Ciudad Vieja with surprising success. But with the expectation that the site's occupation would be fairly short in archaeological terms, my attention turned to issues of use of ceramic vessels as tools, and as communication devices.

Now, why the obsession with ceramics? Ceramics have been studied probably more than any kind of portable (leaving out architecture) type of material culture from archaeological sites. Stone tools have a much deeper antiquity, but once a culture produces ceramic vessels, they typically produce a lot of them, in part because clay and other ingredients are usually closer at hand than particularly good stone for tools. Fired ceramic vessels can break into fragments, but on the scale of archaeological time, they generally don't break down further, and so they preserve in trash dumps and in forgotten corners of buildings. Also, they often incorporate plastic or painted decorative or stylistic elements, in addition to having attributes relating to their use as cooking or serving or storage containers. Borrowing from art history, archaeologists have long realized that these stylistic elements change through time, and for many sites and archaeological cultures, ceramic fragments form the chronological backbone for understanding the rest of the site. They also were tools, used in a number of different contexts for different activities, and can provide information about these activities. Some of those contexts and functions have social and cultural elements to them besides basic mechanical functions, and these elements have been particularly interesting to archaeologists trying to say more about past people than simply when and where they lived. Patterns in use of ceramics, or decorations on the pots, or how they were obtained and distributed, can serve as evidence for more intricate, if at times less certain, discussions of power, gender, ethnicity, class, identity, and other topics with broader interest and importance.

I'll be discussing these sorts of issues here and in my published work. But the reason for this long tangent is to point out that right from the start of my work, I knew that chronology would play an unusual role in my research. On the one hand, a short-period of occupation can be really useful. In this case, Ciudad Vieja allows myself and other researchers working on the site to investigate just the first few years of the Spanish invasion of Mesoamerica. In many other cases, a colonial site is still occupied, and chronological markers are not precise enough (more on that in another post) to narrow things down much less than 50 - 100 years. So in a number of cases, the sixteenth-century is treated as the field of study for the Early Colonial period in Mesoamerica. But this is a fairly long time. During the first generation after the arrival of Europeans, some estimates suggest population dropped 90% or more in Mesoamerica and other areas of contact due to disease, disruption of economic networks, oppression, and war. Spanish colonial policies changed during this period as well, and the kinds of colonists and their institutions changed too. Our work at Ciudad Vieja cannot illustrate or serve to investigate all of that. We don't have occupation throughout this period, or as far as we can tell, immediately before the Spaniards arrived. So making "Before/After" comparisons is difficult with Ciudad Vieja data. Rather, we serve as a time capsule of a sort, of a short but incedibly crucial period in the European invasion of Mesoamerica. We don't have the whole sixteenth-century, but what we do have is a chronologically narrow slice of the sixteenth-century that allows us to say things with more certainty in comparison with other places and periods, and perhaps advance the ability of researchers elsewhere to discern these early years at other sites.

One other point that guides my research is that early San Salvador/Ciudad Vieja is part of the Mesoamerican colonial history and experience. With the exception of a few failed Norse colonies five centuries earlier, Europeans began the colonization of the Americas in 1492. Some twenty-five years later, the first attempts to control Mesoamerica began, with Hernan Cortes' expedition against the Mexica empire being ultimately successful beginning in 1519. The relatively small-scale chiefdoms of the Caribbean were a very different situation than what the Spaniards found in Mexico, and then Central America and later Peru. The people of Mesoamerica had created large urban cities for at least 1500 years before the Spaniards arrived and had been recording dates and other information for possibly 2200 years before Columbus. The cities the Spaniards found and destroyed were larger than anything they had seen at home, something they attested to often. This encounter and disaster in the early sixteenth century is near the very beginning of the period of European colonization of much of the globe, a process that would last for another four centuries and completely transform the world we now know. And in Mesoamerica, Europeans had their first encounter with a highly complex, urban, and literate society of the Americas. They often turned to their dealings with the Muslim caliphates to try and categorize what they found, or to the writings of antiquity, but this encounter would eventually have a profound effect on the European worldview and imagination, and on the global economy and balance of power.

And Ciudad Vieja is a part of the beginning of that encounter. Settled a scant seven years after the surrender of the Aztec capitol of Tenochtitlan, I have repeatedly returned to this fact, that the materials I am studying are the evidence of the very beginning of Europe's colonialism, the very end of prehispanic Mesoamerica, and the origins of the modern world.

No comments:

Post a Comment